Reunions and Tourism

During the 1870s, veterans of the Civil War began to reunite, often on days set aside to decorate soldiers’ graves. Usually held in May, participants in these commemorations adorned cemetery graves with flowers and flags, inspiring what we celebrate nationally as Memorial Day. However, it was not until the late 1880s, about twenty-five years after the end of the war, that Blue-Gray reunions, jointly honoring both Confederate and Union veterans, began to be held. The men attending these events were deeply invested in revisiting the places where they had made history. For the South there were powerful economic reasons for combining reunions, for they drew diverse crowds of men and women to what soon became tourist attractions. Moreover, after two and a half decades, the need for battlefield preservation was evident and federal funding could be attracted through projects that gave evidence that the region was moving past the war. Chickamauga National Military Park was the first of its kind. Its role as a site dedicated to and organized by veterans of both sides helped confirm a reunionist memory of the war that focused on battles and heroism, while ignoring the potentially divisive issues of slavery and emancipation.

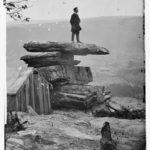

Barton L. Barker.

Barker Walking Cane, ca. 1890.

Photograph Courtesy of the Chattanooga History Center.

This folk art cane was carved by a veteran of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry (U.S.A.), possibly from wood

procured near the battlefield at Chattanooga. Barker, who moved to Chattanooga after the war, belonged

to two Union veteran organizations: the Lookout Mountain Grand Army of the Republic Post #2 and the Union

Veterans League, whose members counted themselves true patriots because they had enlisted prior to the

draft in July 1863.

View Object Details

Reunions gave visitors the chance to understand battle strategies and triumphs as well as providing insight into the suffering of war in a way that no text or visual representation could furnish. For those who could not make the journey, the next best thing was to see the events through the eyes of an artist in large-scale paintings, panoramic photographs, or cycloramas designed to impart the same sort of visceral “aha” moment often experienced upon a Civil War battlefield.

— Celia Walker, Director of Special Projects, Vanderbilt University Libraries; Susan Knowles, Research Fellow, Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University; and Daryl Black, Executive Director, Chattanooga History Center

Further Reading

- Gilbert E. Govan and James W. Livingood, The Chattanooga Country, 1540-1976: From Tomahawks to TVA (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1977)

- Jim Hoobler, Historic Photographs of Chickamauga Chattanooga (Nashville: Turner Publishing Company, 2007)

- Digby Gordon Seymour, Divided Loyalties: Fort Sanders and the Civil War in East Tennessee (Knoxville: The East Tennessee Historical Society, 2002)