John Pope

I n antebellum Memphis, Colonel John Pope (1794-1865) was one of the most successful and distinguished men in the cotton business. After studying law at Yale University and serving in the Alabama legislature, he had become increasingly interested in agriculture. By the 1850s he owned farms in the Memphis area totaling 900 acres. Pope worked diligently at the “science of farming,” using innovative yet practical methods to increase the quality and quantity of his crops. His success was internationally recognized when his bale of short staple cotton was awarded a first-place medal at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. He received a silver medal in 1853 in New York.

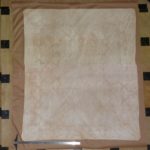

Leonard Charles Wyon.

Prize Medal for Cotton, 1851.

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art; A Gift to the Citizens of Memphis and Shelby County from the Bond

Family.

View Object Details

Pope’s plantation reportedly held $20,000 worth of cotton bales when Memphis fell to Union forces in 1862. Pope, like many farmers in the South, had been urged to “keep every bale of cotton on the plantation” after the Confederate Congress had prohibited the sale of cotton to the North in 1861. But Confederate states had also been given the right to destroy cotton likely to be confiscated by enemy soldiers, so Confederate soldiers were quick to burn the precious bales before the farm was raided by Federal troops. John Pope’s cotton crop was among the estimated 2 1/2 million cotton bales burned during the course of the Civil War. Witnesses recalled that as the Union boats approached Memphis in June of 1862 cotton blazes made the night “as lurid as flames could make it, and the day as hazy with the clouds of smoke as a fog on the river.” 1

— Marilyn Masler, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

1John Hallum, The Diary of an Old Lawyer (Nashville: Southwestern Publishing House, 1895)

Further Reading

- “Col. John Pope was Once Local Cotton King,” Commercial Appeal (22 May 1919)

- Paul R. Coppock, “Three Popes Who Left Their Mark on Memphis,” Commercial Appeal (9 April 1978)

- The Illustrated Exhibitor, A Tribute to the World’s Industrial Jubilee, Comprising Sketches, by Pen and Pencil of the Principal Objects in the Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, 1851. London: John Cassell.

- John Livingston, Portraits of Eminent Americans Now Living: With biographical and historical memoirs of their lives and actions, II (London: Sampson, Low, Son & Co., 1853-1854)

- “Plantation Home Remedies: Medicinal Recipes from the Diaries of John Pope,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 22 (1963)